Shared Horizons of Liberation

“Measures of Distance” by Hatoum and “Where we come from” by Jacir

Abstract

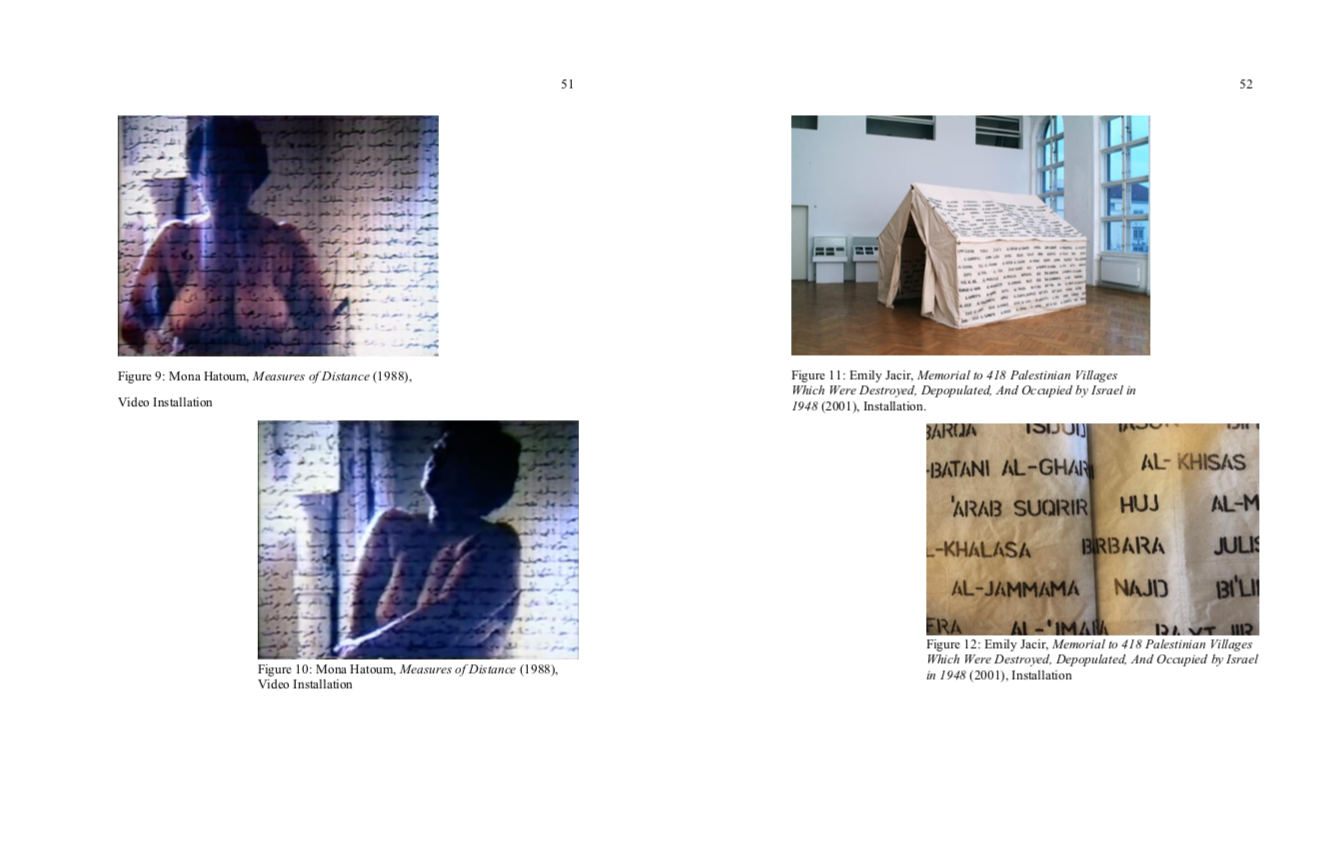

The year of 1948 is known as al-Nakba, the year of “catastrophe” to Palestinian collective memory and history, which coincides with the birth of the Israeli State. Al-Nakba opened irrecoverable gaps and fissures in Palestinian life, as it did in the lives of Mona Hatoum and Emily Jacir, two prize-winner transnational woman artists of Palestinian descent. Hatoum’s and Jacir’s personal and cultural backgrounds and the historical and political context of their life trajectories allow us to understand the issues they address in their works. This thesis shows how Measures of Distance (1998) by Hatoum and Where we come from (2003) by Jacir examine the aftermath of Al-Nakba, including the complexities and intricacies of displacement and the deprivation of Palestinians from attending to their most basic human needs. It goes further to suggest how the artists’ own experiences as the second-generation inheritors of the Nakba are reflected in their work. This thesis shows how in Measures of Distance and Where we come from each artist uses their work to mobilize against the erasure of Palestinian narrative and against the stereotyping of Palestinian as a mass that is devoid of feelings, or as refugees, extremists, martyrs, and so on. They do so by uncovering and highlighting intimate memories, shared traumas, and everyday experiences of Palestinian lives. As Hatoum and Jacir have both spent ample time in the Anglophone West, their work also addresses issues of displacement, familial separation, loss of home, and exile, which cut across and transcend borders and ethnicities.

Introduction

My aim in focusing on the selected artworks of Mona Hatoum and Emily Jacir, two well-known and accomplished transnational artists of Palestinian descent, is to discuss the ways in which their art inscribes a collective history and existence through unearthing personal narratives of exile and of displacement. My hope is that in navigating Measures of Distance by Hatoum and Where we come from by Jacir across the chapters of this thesis I can show how these works of art illuminate the Palestinian displacement and struggle in its multiplicity and diversity. Rather than essentializing bodies according to their origin and current situations, in these works, Palestinian-ness includes all bodies whose life is directly or indirectly affected by displacement, dispersion, dispossession, marginalization, criminalization, and by the condition of exile due to the State of Israel’s structural colonialism and racism. In doing so they not only map out various Palestinian narratives and collective history but also defy the stereotypical representations of the Palestinian cause.

Although the exact boundaries of “Palestine” have been fluid, its existence in Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman times has been clear, and not much different than those established by the United Nations when it described it as a de jure sovereign state in 1948. At that time, it included much of today’s Israel, as well as the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and with Jerusalem as its capital. The people of this land have also been characterized with some fluidity. With the rise of ethnic nationalisms, the term “Arab” has been used both by and about several of its ethnicities, including Muslims, Christians, and Druze, and following several agendas. Throughout this thesis, I use the term “Arab” following the artists’ statements, as a porous term and as a specific approach to inclusive rather than the divisive conceptualization of Palestinian-ness with the purpose of outlining the particularities of contemporary Palestinian experiences after al-Nakba.

For the generation that had lived in historic Palestine and experienced the dispossession of their land, people, culture, and collective identity, dispossession was not new. Although 1948 marked the moment of rupture in Palestinian history, the occupation of Palestinian land and subordination of Palestinians began long before the creation of the Israeli State in 1948, which followed four hundred years of Ottoman imperial rule and the period of the British Mandate (1920-1948). That is to say, even before the birth of the Israeli state, the generations who had lived in historic Palestine before the Nakba were acquainted with the colonial agenda and administration and white supremacist hegemony over its ethnically and culturally diverse groups of Arabs in Palestine; Druze, Christians, Muslims, and so on.

The Palestinian Exodus, that is to say, devastation, loss of homeland, and shared trauma, erased the former divisions inflicted by the British Mandate among Palestinian society, such as among tribes and nobles, peasants and urban populations, as well as poor and wealthy, giving more unity to Palestinian identity. In fact, the generation of Palestinians who witnessed the Nakba have come to realize their similarities rather than differences that they were all displaced, dispossessed, and marginalized by the structural colonialism and racism, “none were masters of their own fate, all were at the mercy of the cold, distant and hostile new authorities” (Khalidi, Palestinian Identity 194). The memories of al-Nakba, of what has been lost, have become an important component of Palestinian narratives and have been passed through generations, mostly through oral culture. From the living narrative and shared trauma of 1948, now primarily based in the diaspora, new generations of Palestinians emerged and generated new Palestinian experiences and narratives of exile, alienation, disorientation, and estrangement, as well as longing, resilience, and dissent through personalizing the processes and longevity of trauma. Measures of Distance (1998) and Where we come from (2003) expose the aftermath of Al-Nakba (1947-49), the complexities of exile, and the deprivation of Palestinians’ most basic human needs.

While each artist interrogates Palestinian history, identity, and experience of displacement and exile in a unique manner, they share a focus on the negotiation of the personal and the collective, the historic and the aesthetic. Both works of art inscribe personal narratives of displacement, loss and exile, and a longing and resilience that resist Israel’s systematic effacement of Palestinian collective existence and history. These narratives are intimate and plural, personal and collective, and they span many displacements and transformations to reveal a shared yet not identical experience of Palestinian exiles. On the one hand, they point out the subjective and diverse experience of Palestinian displacement and struggle. On the other hand, they create shared bonds, an imagined link of communication between dispersed community members despite the bans and restrictions imposed by the structural colonialism of the Israeli State. In Measures of Distance, Hatoum points out the manifestation of violent colonial fragmentation and displacement across two generation by unearthing intimate correspondence with her mother in which they speak of separation, loss, and disorientation. The artist creates a space of intimacy with her mother through female body and sexuality despite the distance imposed by first, her family’s exile from Palestine, second; her own exile from Lebanon. On the other hand, Where we come from documents the differentiating and intersecting experiences of Palestinian displacement and struggle through mundane desires, ordinary wishes, daily activities that exiled Palestinians are unable to fulfill on their own. Jacir provides a collective storyboard of Palestinian displacement, a shared history, and struggle that has grown out from and resists colonial fragmentation.

Measures of Distance and Where we come from operate on the foundational feminist slogan “what is personal is political.” The experience of exile and displacement, that is to say, the Palestinian struggle and resistance for self-determination, manifests itself through what is personal: familial relationships, ordinary desires, mundane wishes, and everyday activities. The works’ seeming lack of political connotations, however, reminds the viewer that the things that most of us take for granted are politicized under the Palestinian circumstances. Their representation of Palestinian displacement turns into a plea for the extension of basic rights for all people. Jacir’s and Hatoum’s works challenge the established representation of Palestinians as they create counter-representations of Palestinians and Palestinian displacement that expose the humanity of Palestinians rather than depicting them as a mass that is devoid of feelings, or as refugees, extremists, or martyrs.

Chapters;

Mona Hatoum: An Introduction to the Artist’s Life Trajectory

Measures of Distance: The Realm of Private Sphere

Emily Jacir: A Brief Look into Artist’s Life

Where we come from: The Realm of Unfulfilled Desires

Conclusion: One Last Thought

PS: Anyone who are interested in reading the rest of the chapters can always get in touch with me via here. I would be happy to share and hear your comments.