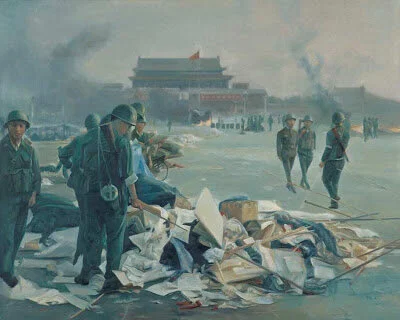

June 4th 1989, Tiananmen Incident

Reflections on Cultural Dimension

“It is in between— between the visible and the invisible, the material and the immaterial, the palpable and the impalpable, the voice and the phenomenon. The ghost is that which could not be seen in the panoptic spectrum and it has many names in many languages: diasporists, exiles, queers, migrants, gypsies, refugees, Tutsis, Palestinians. “”

In the spring of 1989, former Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang, who had been accused of bourgeois liberalism and forced to resign by Party members, died of a heart attack. His death led people to pour out into the street to commemorate him, but also triggered an expression of discontent among students, workers, intellectuals, and many ordinary citizens against the existing party policy. In turn, students all around Beijing mobilized and marched to Tiananmen Square the night before Hu Yaobang’s memorial service, which took place in the Great Hall of the People. Among the 100,000 students who gathered on the square, three students stepped forward to the stairs of the Great Hall of the People to convey their petition and demand a dialogue with party officials. They knelt on the steps as a sign of respect and waited for thirty minutes to be heard but received no response.

Disappointed and feeling abandoned by their officials students began the nationwide boycott that today is known as the June 4th Movement. Although one of the critics of this history being recorded mostly on Beijing, throughout the country massive demonstrations took place that demanded not only the promise of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in 1978 but also democracy and freedom of speech, Until the military intervention on 4th of June that ended with violence and death on both sides, the square hosted several thousand people, concerts, speeches, Goddess of Democracy --a symbolic sculpture of the movement--, a hunger strike and many more historic moments. Today these have slid into oblivion from the collective memory of Chinese people because of CCP’s ideological campaigns. Thus, this very fact of being erased from the collective memory of such a vital moment, both politically and culturally, in China’s official history led me to do this research paper. Although I should clarify that this retrospective study will be my effort to understand the reflections on cultural dimensions of the movement. In a nutshell, this paper will be focused on actors of the incident and cultural reflections on the memories of survivors to see that what can remain in our minds when people are not allowed to speak, know, or even mourn.

Connection with May 4th 1919 and June 4th 1989

May 4th, 1919 is another milestone in China History that not only left a mark both in the memory of people but also had been memorialized by being depicted on Monument to the People’s Heroes. May 4th was a protest by the students of Beijing against the Treaty of Versailles and China’s weak stance against imperialist powers, especially Japan. Similar to June 4th movement intellectuals played an essential role as a voice of the people but its aftermath was distinctly different from June 4th. In both cases, intellectuals rose up in order to warn their authorities regarding China’s precarious situation, but May Fourth’s impact echoes in history in Mao Zedong’s words “We are awakened! The world is ours, the nation is ours, society is ours. If we do not speak, who will speak? If we do not act, who will act?” (Lim, L. The People’s Republic of Amnesia, pp. 33) while June 4th is a “counterrevolutionary” attempt that disgraced China and its officials.

As an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement, May 4th in its essence was a body of patriotic people that demanded national salvation (jiuguo) by adapting Science and Democracy. Accused of destroying traditional ethics, arts of China, and Confucianism, Chen Duxiu, a scholar, writer, editor, and an intellectual wrote in New Youth;

“We have committed the alleged crimes only because we supported Mr. Democracy and Mr. Science. In order to advocate Mr. Democracy, we are obliged to oppose Confucianism, the codes of ritual, chastity of women, traditional ethics, and old fashioned politics; in order to advocate Mr. Science, we have to oppose traditional arts and traditional religion; and in order to advocate both Mr. Democracy and Mr. Science, we are compelled to oppose the cult of the “national quintessence” and ancient literature” (Wasserstrom N. J. & Perry J. E. ( Eds). (1994) Popular Protest & Political Culture in Modern China. pp. 97, Westview Press).

The emphasis on Science and Democracy rose from the need for an intellectual renaissance, economic modernization in other words national salvation and enlightenment. In 1989 many students believed that they were also carrying out their brothers’ and sisters’ demands in 1919. In both circumstances, as a voice of people for the rights of people, intellectuals and students called for action toward a more progressive, democratic, modern China and improvement in material standards of living.

The Role of Intellectuals

It is important to look closely at the role of intellectuals and their motivation for rising up since the leading figures of the movement almost entirely are the intellectuals and students. Once I embarked on my effort to make sense of the moment, I encountered a great deal of study on the political role of intellectuals in China and their identity crisis throughout its history. As they were on the center stage of June 4th, I truly believe in their role in shaping China’s history with their great enthusiasm as the conscience of the people. However, I also came to realize that their conceited attitude towards ordinary citizens, workers, or even each other caused unpleasant moments in the square from time to time. Thus, this, among many other factors, could be one of the reasons for the failure of the movement. It is clear that understanding the intellectuals’ position in China’s past is one of the key points for understanding the Tiananmen Incident.

It was Mencius, Confucius’s disciple, who first codified the Chinese intellectual’s duty to society in the famous adages, “ Those who work with their minds are meant to rule; those who work with their brawn meant to be ruled” and “Those who know are the first to awake; the enlightened awake the others” (Schwarcz, V. Memory and Commemoration: The Chinese Search for a Livable Past, pp. 171).

This very self-position of intellectuals as a voice and conscience of the people inevitably brings the illusion of superior status, which in turn, causes their social isolation from ordinary life. Education as a tool for ideology and the creation of national identity and attachment has always been a crucial tool for the ones in power not only in China but also in every other country. Through the institutionalization of education and examination system, China’s intellectuals have always had close relations with the regime of power in order to obtain an official position within the state control. Moreover, this dependence on the state clearly creates a sense of loyalty and personal ties with state power that, in turn, make impossible to think of China’s intellectuals as actors who are independent and freed from constraints of ideology but closely relates the notion of being an intellectual with power itself.

In the era of the Cultural Revolution, Mao aimed to reverse their position within the society by blaming intellectuals for being elitist, bourgeois liberals, and he criminalized them. The degradation of intellectuals prevents them from commenting on political issues and caused them to lose their social status. Moreover, by tightening the CCP’s grip on intellectuals, Mao prevented any critical comments against CCP and created affirmative intellectual strata who were strongly bond the CPP’s decision making thus disabled to be autonomous strata. Although Deng Xiaoping’s reforms healed their position in the society in comparison to Mao’s era, intellectuals’ social contract with the state for better jobs, housing, health care, and so on remained. Therefore, intellectuals remained under the control of CPP policies. In return, they regained their status as patriots and once again engaged in their intellectual pursuits. According to Cao Changqing, who is one of the Chinese intellectuals that took part in China Symposium '89, Bolinas, California, 27-29 April 1989 and was denied permission to re-enter China for calling Deng Xiaoping’s retirement, “Chinese artists and writers, as a part of the intellectual stratum, have always belonged to the class of officials. They have never had an independent spirit or sense of self-worth. They have always wanted to be at someone’s service” (Lee, Leo Ou-fan. Art and Activism. 1989). Although intellectuals did not cease being bound up with the state, concurrent demonstration in Beijing in the spring of 1989, I believe, proved that Changqing’s statement was unfair to intellectuals.

By neglecting the fact that China partly opened its doors to the West during the reform years, capitalism and its profits also found a place within society. Feeling deprived of opportunities and autonomous life, China’s intellectuals and students sought democracy in order to obtain freedom of expression, self-liberation, and economic improvements. By taking support from citizens and workers, student leaders acquired the position of rock-stars and adopted the ritual of self-sacrifice. They even wrote their last testaments as a tragic symbol of their patriotism and determination to save China from the oppressor regime. The persistence of the suppressive bond between the state and intellectuals could be traced not only in their repetitive emphasis on patriotism and belief in China but also when a group of students turned over their fellow students who attacked Mao’s portrait to the police force. This, to me, shows the great internalized pressure that taken place for years in China and the intellectual’s attachment to the class of officials. As they were appearing in broadcasts all around the world, students got caught up in the “cult of a hero” and for some people, their actions on the square were moving away from being democratic. Because of student’s distorted image that shaped in times in the minds of Chinese people for sitting down on the square without doing anything, having fun with the rock concerts and ascending power plays among students against each other, leading intellectuals took initiative and started their own hunger strike. By doing that they hoped to invite students to recall their primary aim to call for democracy, not just solely oppose the government. Thus, the intellectuals’ hunger strike began on June 2nd but did not last. On the evening of June 3rd, troops attacked the square, wiped out everything they encountered, and killed or injured some unknown number of people, even the bystanders.

From the beginning of the June 4th movement, students, workers, and intellectuals on the square were pointed out as counterrevolutionary rebels by CCP officials and devalued as lovers of the west, agents who were aiming to break down China. The deactivation of intellectuals by imposing force once more caused the alienation of intellectuals because even though they saw themselves as patriots, China wanted to erase them from its history. “ The government’s decision to turn arms on its own people sent out a clear message that violence was an acceptable tool” (Lim,L. (2015). The People’s Republic of Amnesia Tiananmen Revisited. p.173, New York, Oxford University Press.). In order to maintain its power and authority, the CPP used every force it had and embarked on cleansing the enemies of China by arresting, interrogating, erasing, and reconstructing every memory regarding this unprecedented seven weeks. Therefore, what was left behind to the survivor of June 4th was the haunting truth of the movement: hopelessness in terms of freedom, exile, being hidden in the underground, and new constraints on one’s mind. During the upheaval of the movement, as Wu’er Kaixi put it: “ All our shut-down senses were wakened at that moment (the death of Hu Yaobang). We became very political overnight” (Lim, L. (2015). The People’s Republic of Amnesia Tiananmen Revisited. p.67, New York, Oxford University Press) Now the youth of China were forced to be amnesiac overnight. The fear of chaos and instability led CPP to take precautions towards any commemoration of June 4th as extreme as banning to let fly a dove on the day of the incident. After a massive ideological campaign, CCP once more restated its power by reminding people of China that as long as they obey and serve its regime of truth, intellectuals will be allowed to live relatively free and allowed to pursuit intellectual positions. We owe our knowledge of Tiananmen to those who were able to flee from the country and hold on to their memory to let people know what happened during the days of 1989. The ones who remained in China are still under constant surveillance even after many years, just in case, they dare to speak of their memories.

As Mirzoeff in his article Ghostwriting: working out visual culture states “It is in-between-- between the visible and the invisible, the material and the immaterial, the palpable and the impalpable, the voice and the phenomenon. The ghost is that which could not be seen in the panoptic spectrum and it has many names in many languages: diasporists, exiles, queers, migrants, gypsies, refugees, Tutsis, Palestinians. “(Journal of Visual Culture, Vol 1(2): 239-254) In this case the ghosts –- victims of sovereign authorities-- were students, young soldiers, workers but the question is how one can save these ghosts from the abyss of amnesia to bring back their memories, to remember that they were once alive and breathing? For this reason, I believe the work of arts from the witnesses of the movement becomes crucial to bring the past into the present. From this point, I will be examining one sculpture that was made during the demonstrations as a symbol of their demand and some paintings which two of them specifically depict the incident. The other two which are not directly related to the memories of the spring of 1989 are being chosen because of their sensational features for being pointing out CPP’s lasting repressive regime after many years.

Goddess of Democracy

The information regarding the Goddess of Democracy that I have had mostly relies on a witness to its creation, Tsao Tsing-yuan, who was a former student of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. I found that piece of art very exciting and significant as its very presence shaped the movement’s momentum. For the grand demonstration on May 30 students of fine arts were asked by the Federation of Beijing University Students to create a statue in three days. They were expected to create a statue similar to the Statue of Liberty as a signifier of democracy and of their demand for freedom and justice. However, students of sculpture raised their concern regarding its very resemblance to the Statue of Liberty, which carried the risk that the students would be labeled a pro-American movement. Therefore, the students wanted it to have neither traditional Chinese traits nor to be a close replica of the USA version. Created collaboratively, thus not naming a specific artist name as its creator, is one of its magnificent achievements in contrast to a common understanding of how art is produced within individualistic societies. Students used what they have already had, a sculpture of a man grasping a pole with two raised hands. “Their aim was to portray the Goddess as a healthy young woman, and for that, again, the Chinese sculpture tradition offered no models. What they turned to was the tradition of favor within the Central Academy’s Sculpture Department, the Russian school of revolutionary realism, and specifically the style of the woman sculptor Vera Mukhina, whose monumental statue of ‘ A Worker and Collective Farm Woman’ … is still much admired in China.” (Wasserstrom N. J. & Perry J. E. (Eds). (1994) Popular Protest & Political Culture in Modern China. p 143 Westview Press)

Although Chai Ling’s presence as commander of Chief, suggests that the movement included a feminist perspective of the movement, in fact not a single demand was conveyed regarding the improvement of women’s rights. Because Chai Ling said“ next time it’s human rights for women,” and gender discrimination was postponed until more important issues had come to a solution. In fact, during the demonstration days, even as women supporters were being seen as leaders, they were also perceived as groupies by some of men students. On the other hand, the goddess also conveyed the message that students also placed importance on strong, independent women figures.

The choice of its location, to me, has two fascinating dimensions that show the movement’s creative resistance. First, by placing it face to face with Mao’s portrait students clearly challenged one of the most powerful figures in China’s history. The Goddess’ gaze on the Forbidden City frankly emphasized that we-– the people of China—are watching you, our eyes are opened. The Goddess of Democracy said to the CCP, in effect, “You will fall from power, we will still be here.”

Another interpretation of the sculpture’s female gender might be its symbolic challenge to the patriarchal structure of the government. It is not known that if the students aimed to raise a feminist perspective while creating the Goddess of Democracy still, it might be possible that it’s being female raised in some people’s mind an inquiry regarding the very male body of the government. If not, it is still fascinating that the figure of a woman looked into the eyes of officials as a symbolic representation of the students. This might not have changed anything, but it remained in the authorities’ memory of the movement even though it was breaking down into pieces.

How Can Restore the Memory of Tiananmen?

It is not surprising that any authority will try to reshape, reconstruct or even erase evidence of its own weakness. The illusion of power has always been a core element of the intoxication with power that gradually causes the authoritarian to lose touch with reality. Thus, the CCP’s launch of an ideological campaign against the June 4th movement and its actors will never be legitimate, but it is understandable. To repress the reality of June 4th and the ones left wounded by the death of their beloved ones, by the memory of their own government using guns on its people, CPP sometimes desperately banned any symbolic simple things as in the case of a white dove. However, more desperately the CCP banned and chained every single memory of painful mourners. “Even this most personal of acts has been made political by the government’s interdictions.” (Lim, L. (2015). The People’s Republic of Amnesia Tiananmen Revisited. p.120, New York, Oxford University Press.) On the tenth anniversary of her son’s death, Zhang Xianling, a member of Tiananmen Mothers, which includes families, relatives, and the friends of 1989’s deceaseds’, held a commemoration for her son on the spot he was murdered. The next year she was no longer allowed to go out on the day of her son’s death. The surviving victims of June Fourth were deprived of mourning, which is a part of a healing process after a loss, and were once more traumatized by their leaders. The massive ongoing official effort aims to dissolve the victims’ memories in order to maintain the stability of the country and avoid any responsibility for the deceased. For some people, it was simply an effort to move on and not be haunted by the past. However, history does not go away. It is there, still in the present, only it is made invisible by those who do not want to see it.

On the 25th anniversary of June 4th, Chinese officials were still taking various precautions in order to prevent the revival of memories. Many artists, human right activist, and intellectuals were detained and interrogated by the official forces for many so-called reasons. As Bao Tong, former Director of the Office of Political Reform of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, puts it: “ barometer of the leadership’s fear: fear of the people, fear of the legacy of untrammeled growth, and fear of their own history” (NPR, June 4: The Day That Defines, And Still Haunts China, June 3, 2014) Therefore, the detention of Chen Guang, a former soldier turned into an artist, on the evening of June 4th, 2014 came as no surprise. Guang, who had been seventeen years old in 1989, was so haunted by the memories of those days that his works aim to force ” viewers to admit the existence of the events” (Lim, L. (2015). The People’s Republic of Amnesia Tiananmen Revisited. p.21, New York, Oxford University Press.) It might be because of this aim that his paintings of Tiananmen are fairly realistic in terms of its style. He paints what he has seen and witnessed during those days in a way that almost presents documentary journalistic visuals, which makes sense after learning that his duty at the time of the movement was recording the incidents for army records. It could be also argued that by depicting his memories, Guang is confessing his sins not because he performed any violence against demonstrators but simply because he was there under the control of authorities. Undertaking the responsibility of proving June 4th, Guang cleanses his conscience and releases the haunting images in his memory.

Among this small circle of artists, another person who is known for depicting Tiananmen is Yan Zhengxue. Yan’s memories regarding the authority’s violence date back to the founding of the CCP. Oppressed by the regime for a long period of time, Yan harbored a great sense of dissatisfaction towards the authoritarian structure of the state. Being imprisoned in a labor camp, Yan created 89.6!!! Tiananmen which is, to me, an incredibly dark but fascinating narrative. As we look carefully at the propaganda images in China, we will more than likely to encounter a depicted sun sometimes as an aura of Mao, sometimes just as a symbol of a bright future. Turning CCP’s symbolic glimmering sun into a dark hole Yan clearly conveys his perception of the CPP's impure policies. The annihilated land he depicts leaves the impression of hostility in those days that creates the feeling of uneasiness for a viewer so that she/he can at least imagine what was it like to live and survive from Tiananmen. Moreover, by saying that the goat “ represents the obedient ones, the only ones left alive” Yan not only sharply criticizes others for staying alive, he subtly criticizes himself.

Zhang Xiaogang was born in 1958 therefore, he had already seen enough during the years of the Cultural Revolution, his paintings drastically reflect the fragmentation of one’s mind after the Tiananmen Massacre. He utters those days “I was pulled back into reality, awakened from my dreams” yet, there is something in his paintings that it is clear he is still haunting by this disillusion. Turned those days into creative works of art, he depicted a series called “ Reincarnation and Nightmare No 1.” What gets my attention is the sameness and stillness of his figure as if they are all the same person who was frozen in a particular time and in a particular situation yet we don’t know who are they, where are they. In his painting The Survivor, the distorted human body conveys the feeling of shattered lives of survivors who are still alive yet not complete. He is there, but also he is not. He is present but also absent. The empty eyes and the posture suggest that his thoughts are unpleasant and also gloomy. It is almost we - as viewers- going to hear him sigh deeply in a moment as him to release whatever feeling he has. Yet we cannot. This expectation that will never come true deepens the feeling of despair in him. As a spectator instinctively one yearns to reach his shoulder and comfort him. On the other hand, his gaze suggests he might not ready to release himself or communicate with them.

In Lost Dream: Man with a Crown of Thorns we encounter almost the same man before but the way he stands and looks is different than the Survivor. This time his body preserves its unity so that it suggests he is not distorted as the Survivor even though they are almost identical. The thorn on his head and his neat clothes suggest that he, in a way, belongs to other social strata. The stillness in the eyes is continual but this time it is harmonized with recklessness. In the background we see very small human heads, though, the man does not seem aware of it or even care about it. He holds a dead sheep head almost in a way he is petting it. The dead head might be interpreted in both ways. If the man represents CPP officials first, the head might be represented the slaughtered ones or second, it might be the symbol of Chinese people who has blind obedience in CPP. In both interpretations, Xiaogang depicts very well his anger and disappointment towards the history of 1989.

Another artist that could not fall into amnesia is Chinese-born-Australian Guo Jian who was arrested only three days before the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen by being accused of visa fraud when in fact he already had a valid visa. He was supposed to be able to come back soon but then on the way, he learned that he was going to be away more than he has been told. Behind this so-called reason what lies is most likely his latest sculpture of Tiananmen Square. Even though the work has not been displayed, the presence of work was already enough to threaten CPP officials for some reason. I say for some reason because different than other mentioned work this particular work has no specific relation to the 1989 massacre. In fact, as the artist himself states in several interviews this particular work is about the urbanization and chancing face of the Chinese landscape. Covered with uncooked meat, this diorama of Tiananmen Square forced to be destroyed by the artist while he was filmed by the officials. As being a witness of the June 4th 1989 Massacre, it might possible that this work of art is reminiscent of those violent days yet it is not articulated by the artist himself. This means that there are no clear critics towards the CPP’s 1989 policies however, the way the CPP is perceived this work of art is related to its own policies. Does this mean that by interpreting the work in terms of government violence, CPP is self-aware of its pernicious implementations and takes this work as a reading of its own violence? If so, we could say that even though the people of China were forced to be amnestic in terms of June 4th, in terms of the Chinese political realm June 4th is considerably alive.

The last artist that will be mentioned in this paper is, for many, almost a celebrity in art world for his controversial figure. The artist Ai Weiwei, well known for his outspokenness, was subjected to incarceration, violence, constant surveillance by State officials since before he was born. His family, first, were accused of being leftist by the Nationalist government later on they were accused of being the rightest during Chairman Mao’s era. Although I find no trace of him being witnessed to the 1989 Movement, throughout his work Weiwei is one of the fiercest critics of State power, particularly Chinese politics. One of his sensational works “Study of Perspective Tiananmen Square” dated 1995, is a photograph of his middle finger. In the background, it is not so clear but looking carefully one realizes that the finger poisoned against The Gate of Heavenly Peace in Tiananmen Square. It is no surprise that he was interrogated regarding his aim to take this photograph. He has no hesitation to speak out against the Chinese repressive regime and any kind of state power as we can understand from his continuing middle finger series in many other countries. Weiwei is a clearly political activist. He is mentioned in this paper, to be honest, not because his work of art speaks to me regarding the incident but because of his bold personality to show what he thinks in spite of the suppression. As a famous figure by shattering the obedient Chinese stereotype, he should be taken credit for his courage not to taking a step back from what he knows, what he sees, what he experiences as a Chinese-born artist.

Conclusion

The violent suppression of the Tiananmen Massacre is not an anomaly. June 4th 1989 Movement in terms of their association with the May 4th Movement in 1919 was not only a threat to China’s political stability for that very moment but also a challenge to CPP’s very foundation. Once digging into this period of time one understands that to fully comprehend this particular movement, we should also understand China’s political actor and their reference point. In terms of June 4th this reference point seems like May 4th for both sides. Students’ patriotic rhetoric referring to martyrs of May 4th and their calling to democracy and enlightenment led a great sense of commonality and similarity between generations. However, also “ the CPP has attached its own special meaning to term by arguing that the intellectual and political ferment of 1919 led directly the founding of the party”. (Saich T. (1990). The Chinese People’s Movement. New York, M. E. Sharpe, Inc.) Thus, other than invading the physical space in Tiananmen Square where one can see the memorial of 1919 martyrs the students of the 1989 Movement had challenged to CPP’s essence. Both sides’ own identification with May 4th, in turn, turned this particular movement into a fight over a historical movement in their history that left a great mark on China’s political climate.

In the midst of such incidents, history repeatedly shows us that the one who has the guns, tanks, thus the power suppresses the ones who have nothing other than their bodies and minds to resist. More importantly, what is really being good for the future of the countries determined not by the people but who hold the power to control those people. Thus, what has been left us to remember and protect the memories of the people who were witnessed and been subjected to suppression in order to be able to read the political implications of an ideology of power. It should be important to cite that such suppression was not the first and will not be the last one in close future not in only China but also around the world. Therefore, this paper does not aim to regard CPP as singlehandedly responsible for the massacre but aims to see the full picture of the consequences of the ideological power and its effects on this particular time in the past.

Reading history is a two-edged sword depending on who writes the historical peace, what is the position of the writer, what sources have been used but most importantly what the writer’s relation to that specific issue. From my standpoint, this particular movement is simple as about the people of a country who rightfully demands a dialogue with no guns but who were welcomed with guns. There are many stories out there that allege different speculations on the student movement. We can choose what we want to believe and what we want to see. As Meike Bal states in her book called Of One Cannot Speak “History in its guise as willful amnesia and its aftermath- the history of the present in which history vanishes- leaves its scars only for those who care to see them, helped by the artist who insists on showing the scars”. This is why I think it is fair to say that in this paper I deliberately choose to focus on the scares of students, workers, intellectuals, ordinary people, thus, on the scares of their collective memory and some of their creative reflections.

Briefly Important Moments in China History

October 1, 1949- Mao Zedong declared the establishment of People’s Republic of China after a long term civil war between Nationalist Party Kuomintang (KMT) and China’s Communist Party ( CCP)

Cultural Revolution 1966-76- This ten-year period in China’s history opens rich controversial discussions in various fields of study. Also known as “the ten years of turmoil” Mao called on China’s youth to challenge the existing bourgeois values and lack of revolutionary sprit. This also led to the birth of the Red Guards, who attacked intellectuals, burned books, and destroyed everything that was not seen as leftist. For many, the Cultural Revolution still holds a vital key to understanding China’s cultural and political position.

1976- Mao Zedong died on September 9. Deng Xiaoping was were still in charge during the spring of 1989 rose to power.

1978- Deng Xiaoping launched reform policy including agriculture, industry, science and defense. Between 1978 and 1979 people of Beijing were allowed to put posters on what is called Democracy Wall to criticize and point out the issues that they were not satisfied with as people of China. On January 16, 1980 Xiaoping declared the cancelation of Democracy Wall because he was personally being criticized and his authority was being questioned.

1981- Hu Yaobang became the Party General Secretary

1987- Accused of being weak and bourgeois, Hu Yaobang was forced to resign from his post. Zhao Ziyang became the General Secretary of the Communist Party, and Li Peng the Premier.

1989- April 15, Hu Yaobang died.

April 17, First Student March to Tiananmen.

April 22, The night before 22nd April, the day before Hu Yaobang’s memorial, 100,000 students gathered on Tiananmen Square. Students tried to convey their petition and demanded dialogue with Premier Li Peng.

April 26, People’s Daily denounced the movement as turmoil which for students was a great insult to their patriotism. They called for an apology.

April 27, Reacting against People’s Daily, massive demonstrations took shape.

May 13, Having no response for their call to dialogue, hundreds of students began their hunger strike on the Square. By doing that, student declared their determination for dialogue. If necessary, they were ready to sacrifice their lives for China.

May 15, USSR President Mikhail Gorbacyev came to Beijing. Because of the demonstrations, Gorbacyev’s welcome ceremony took place at the airport. The presence of Gorbacyev is one of the reasons that the demonstration gripped the attention of international journalists from all around the world who were already in China to broadcast the meeting.

May 18, Students’ demand for dialogue was finally granted. Premier Li met with student leaders. One of the leading figures of June 4th Wu’er Kaixi came from his hospital bed with his oxygen tank. The transcripts of this conversation can be read on the website of the Heavenly Gate.

May 19, Students ended their hunger strike on its seventh day because of the rumors regarding martial law.

May 20, Martial law was officially declared in Beijing. From that moment on the troops tried to enter the square several times but were blocked by citizens and worker unions.

May 29, A statue of the Goddess of Democracy was placed in the square where she was face to face with Mao’s portrait.

June 3rd, Four intellectuals Liu Xiaobo, Zhou Duo, Hou Dejian, and Gao Xin started their hunger strike to criticize both the CCP’s un-democratic position and the students.

June 3rd- 4th, Troops opened fire on civilians, tanks smashed and destroyed everything on the street. Massive cleaning on the street took place to erase every minor memory of the movement. “Over the years the army was seen as a true People's Army: from the people, of the people, and for the people. The Party said that the army was like fish and the people like water: fish can't live out of water.” (The Gate of Heavenly Peace, 01.40.17) but now it was the same fish that was wiping out their very own life source.

June 9th, Deng Xiaoping announced the suppression of “counterrevolutionary rebellion”. Many were killed and arrested. Those who were enough lucky to escape are still in exile.